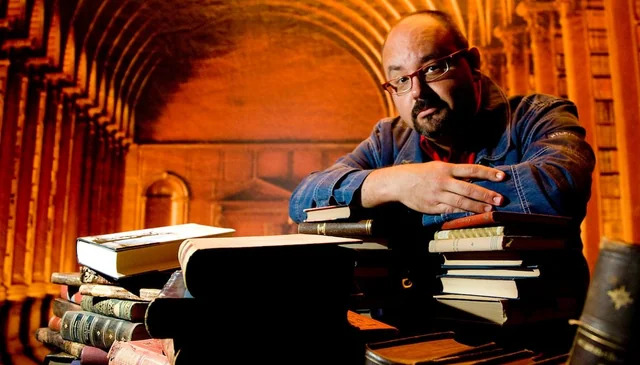

Что такое хорошо - Евгений Семенович Штейнер

Книгу Что такое хорошо - Евгений Семенович Штейнер читаем онлайн бесплатно полную версию! Чтобы начать читать не надо регистрации. Напомним, что читать онлайн вы можете не только на компьютере, но и на андроид (Android), iPhone и iPad. Приятного чтения!

Шрифт:

Интервал:

Закладка:

One of the incidental results of this book is bringing numerous previously marginalized authors, artists, and art onto the center stage (there is a biographic section at the end of the volume that gives information on the life and work of 67 artists mostly unknown in the West). Drawing upon books from Russian State Library, private collections, and publisher’s archives the author makes the artistry of children’s books accessible

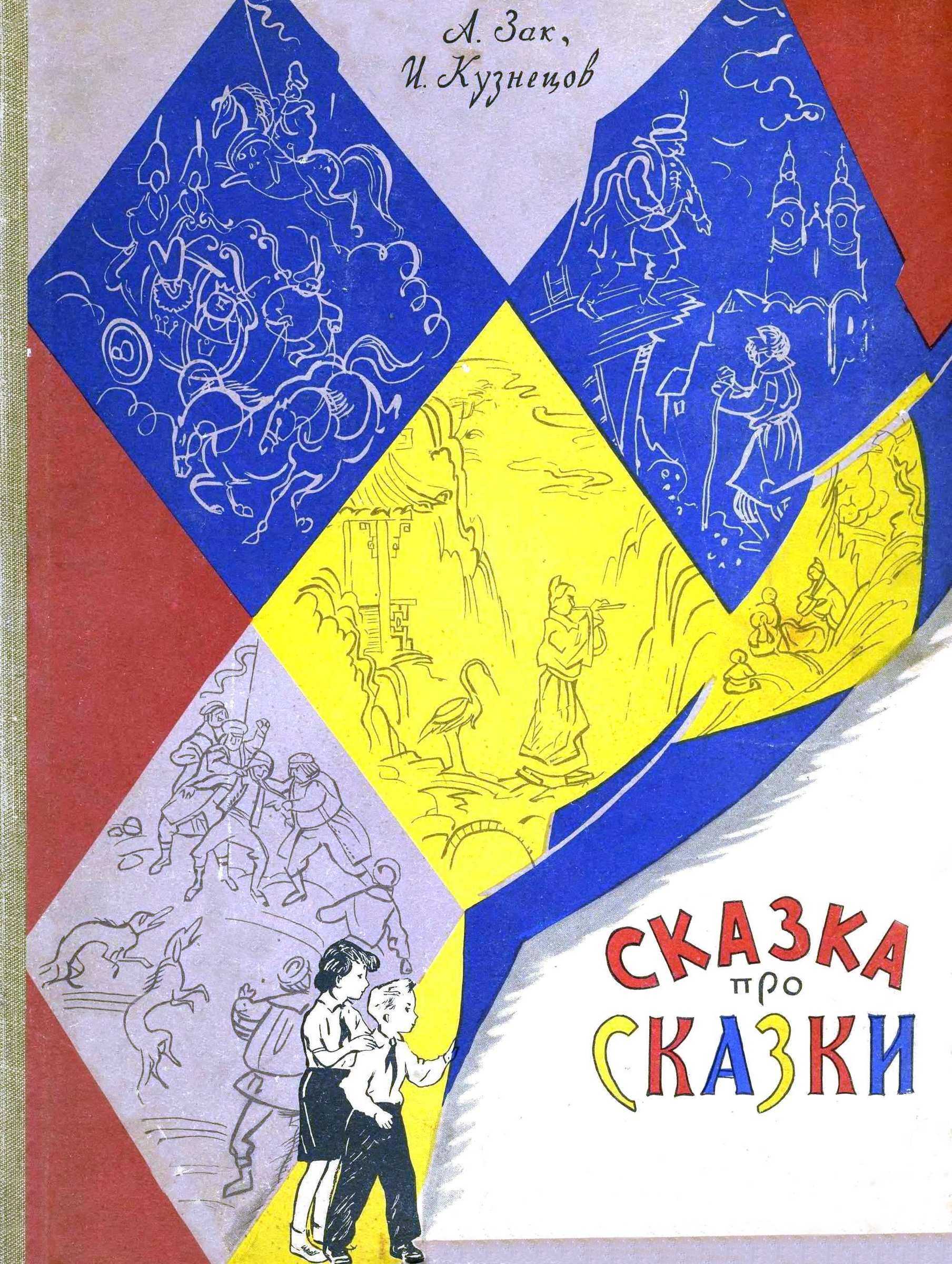

In the preface and introduction, the author explains why artists eager to aesthetically and socially shape the «New Man», and earn a paycheck, gravitated to children’s book illustration. His task was to examine the «fundamental artistic, aesthetic, and spiritual stereotypes of the late 1920s and early 1930s» in forming avant-garde illustrations of children’s books. The author contends that during the early Soviet period, Constructivist and other Left illustrators embodied the new regime’s objectives in the genre of children’s literature, which proved an ideal ground for elaborating the new principles of graphic design, blending archaism and futurism.

The First chapter, «Laying Out the Boundaries: Architects of the Constructivist Project», traces origins, tracks developments, and spotlights key figures in the country’s concerted effort to forge a visual image of the children’s book in harmony with purported Soviet reality. The author begins with examining works by Natan Al’tman, Yury Annenkov, Vera Ermolaeva, and Elena Turova – all members of the short-lived Segodnya (Today) artists’ collective (1918–1919). Acknowledging the role of such internationally famed artists as Lissitzky, Malevich and Tatlin, the further discussion focuses on the lesser-known Vladimir Lebedev and Nikolai Lapshin, while simultaneously taking into account Samuil Marshak’s and Kornei Chukovsky’s verbal texts and the relevance of Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin and Vladimir Konashevich’s artwork to the new aesthetics of «dynamic angles, shifts, collisions, and movement», and dislocation. In a section on diagonal composition, the author maintains, «the regime, itself an artist of social relations, recognized the existence of a metaphysically hypostasized concept, uklon (in politics, a deviation; in other realms, a slope of declivity), but in its capacity as supreme ruler thought it necessary to oppose it».

The Second chapter, «Elements of the Constructivist Project», assesses the «production» books that dominated children’s literature in the mid-1920s and adopted types of narratives manifestly indentured to Soviet ideology: poetry and prose explicating the manufacture of goods (e. g., Where Dishes Come From); stories and verses about trades (e. g., Vanya the Metalworker), sundry industrial phenomena (e. g., Blast Furnace), mass kitchens (or «factory-kitchen»), and assorted machines, with the steam engine as the major literary hero. Children likewise appeared as positive heroes, mythologized in their origins and achievements, and appropriately monumentalized in the illustrations that duplicated iconographic schemas mapping the Great Leader statuary. The author pinpoints the isomorphism between the stereotypes of social behavior and deportmnt of bodies in Constructivist illustrations for children, on the one hand, and «elevated» adult Soviet art of the era, on the other: both focused on labor, internationalism, revolution as a destructive creation, social reorganization through technology, collectivism, athleticism, and ritual cleansing.

The Third chapter, «The Production Book: Locomotives and All the Rest», turns to the locomotive as the apotheosis of the heroic new world, the magic carpet of Soviet modernity. The author analyzes here how «quasi-religious, Romantic notions of a rapid transition from the past to the future in a „historically short period“ evoked visions of dynamically accelerated time». Artists, including Galina and Olga Chichagov, Boris Pokrovsky, Alisa Poret, Boris Ender, Nikolai Ushin adopted the locomotive as a metaphor for a society and a culture moving towards permanent revolution. The wide-ranging discussion here incorporates various cultural tendencies, both long-standing and specifically Soviet, to reveal the dimensions of, and permutations in, Russia’s romance with such binarisms as human/machine, disorderly nature/efficient order, ascetic simplicity/lush excess, etc. As throughout the volume, the author cites from Party resolutions, articles, monographs, art catalogs, poems, and songs as he investigates the texts and illustrations glorifying the transcendence over temporality and space that obsessed early Soviet mentality.

The Conclusion offers a preview of the shift in sensibility that would occur during the 1930s, and, specifically, the Central Committee’s resolution «On the Publishing of Children’s Literature» (December 9, 1933), which resulted in the consolidation of children’s publishing into Detgiz, charged with the task of making «decisive improvements in design, rooting out shoddy hackwork and formalist frills». The avant-garde – and broader, Left – experiment in abstract minimalism ended with its chief practitioners either incarcerated (e. g., Vera Ermolaeva, who died in a camp in 1938) or self-transformed in accordance with the demands of the Stalinist empire (e. g., Vladimir Lebedev). The wholesale embrace of utopia, characteristically, culminated in decimation.

The Last chapter, «The Foreign Coda», expands the scope of the analysis by giving a brief exposure to the similar tendencies in the children’s books in the West: mostly in the United States and also in Germany and France. In the 1920s–1930s many modernist and/or politically left authors and artists, as well as innovative liberal editors, worked in the field of children’s book publishing. Numerous parallels between the Russian and Western artists provide a broader artistic and cultural context to the main subject of this book: the early Soviet experiment in making new children’s books and new children. It places this experiment, previously seen as an exclusively revolutionary outcome, into the mental milieu of the early 20th century Modernism and its infantilist strategy.

Отзывы

Это своевременное и широкое по тематике исследование в области изучения детской литературы. Сделанное Е. Штейнером сопоставление культурных, политических и литературных аспектов мышления открывает новые горизонты в исследовании советской авангардной детской книги 1920 гг. и ее воздействия на педагогические и художественные устремления того времени. Тонкий анализ ясно демонстрирует особенно важную роль советских книжек-картинок в концепте «Нового человека» в революционную эпоху. Собрав воедино методологические проблемы визуальных искусств, литературы и политики, эта книга открывает интригующее прозрение в дотоле малоисследованную область.

Беттина Кюммерлинг-Майбауэр, профессор Тюбингенского университета, редактор

Прочитали книгу? Предлагаем вам поделится своим отзывом от прочитанного(прослушанного)! Ваш отзыв будет полезен читателям, которые еще только собираются познакомиться с произведением.

Уважаемые читатели, слушатели и просто посетители нашей библиотеки! Просим Вас придерживаться определенных правил при комментировании литературных произведений.

- 1. Просьба отказаться от дискриминационных высказываний. Мы защищаем право наших читателей свободно выражать свою точку зрения. Вместе с тем мы не терпим агрессии. На сайте запрещено оставлять комментарий, который содержит унизительные высказывания или призывы к насилию по отношению к отдельным лицам или группам людей на основании их расы, этнического происхождения, вероисповедания, недееспособности, пола, возраста, статуса ветерана, касты или сексуальной ориентации.

- 2. Просьба отказаться от оскорблений, угроз и запугиваний.

- 3. Просьба отказаться от нецензурной лексики.

- 4. Просьба вести себя максимально корректно как по отношению к авторам, так и по отношению к другим читателям и их комментариям.

Надеемся на Ваше понимание и благоразумие. С уважением, администратор knigkindom.ru.

Оставить комментарий

-

Гость Татьяна16 февраль 13:42

Ну и мутота!!!!! Уж придуман бред так бред!!!! Принципиально дочитала до конца. Точно бред, не показалось. Ну таких книжек можно...

Свекор. Любовь не по понятиям - Ульяна Соболева

Гость Татьяна16 февраль 13:42

Ну и мутота!!!!! Уж придуман бред так бред!!!! Принципиально дочитала до конца. Точно бред, не показалось. Ну таких книжек можно...

Свекор. Любовь не по понятиям - Ульяна Соболева

-

Гость Марина15 февраль 20:54

Слабовато написано, героиня выставлена малость придурошной, а временами откровенно полоумной, чьи речетативы-монологи удешевляют...

Непросто Мария, или Огонь любви, волна надежды - Марина Рыбицкая

Гость Марина15 февраль 20:54

Слабовато написано, героиня выставлена малость придурошной, а временами откровенно полоумной, чьи речетативы-монологи удешевляют...

Непросто Мария, или Огонь любви, волна надежды - Марина Рыбицкая

-

Гость Татьяна15 февраль 14:26

Спасибо. Интересно. Примерно предсказуемо. Вот интересно - все сводные таааакие сексуальные,? ...

Мой сводный идеал - Елена Попова

Гость Татьяна15 февраль 14:26

Спасибо. Интересно. Примерно предсказуемо. Вот интересно - все сводные таааакие сексуальные,? ...

Мой сводный идеал - Елена Попова